-

Hear from Monica Toft, Academic Dean

Learn how Monica Toft, Academic Dean, is shaping the study of global affairs and diplomacy at Fletcher.

Hear from Prof. Toft -

Explore Fletcher academics in action

Fletcher Features offers insights, innovation, stories and expertise by scholars.

Get global insights -

Get application tips right from the source

Learn tips, tricks, and behind-the-scenes insights on applying to Fletcher from our admissions counselors.

Hear from Admissions -

Research that the world is talking about

Stay up to date on the latest research, innovation, and thought leadership from our newsroom.

Stay informed -

Meet Fletcherites and their stories

Get to know our vibrant community through news stories highlighting faculty, students, and alumni.

Meet Fletcherites -

Forge your future after Fletcher

Watch to see how Fletcher prepares global thinkers for success across industries.

See the impact -

Global insights and expertise, on demand.

Need a global affairs expert for a timely and insightful take? Fletcher faculty are available for media inquiries.

Get in Touch

A Microeconomic Approach to Sustainable Development

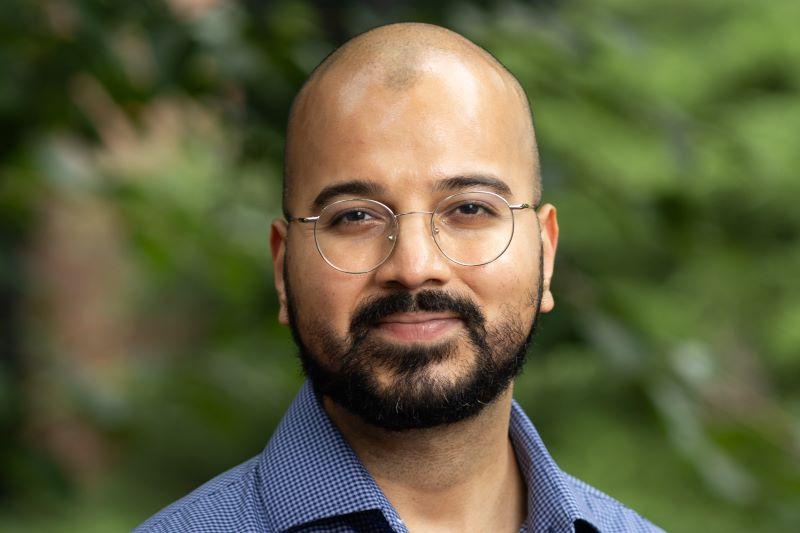

Maulik Jagnani studies topics in environmental health and human capital in developing countries

For Maulik Jagnani AG12, teaching at The Fletcher School is a homecoming.

Jagnani, assistant professor of environmental economics, earned his master’s degree in economics at Tufts University. His studies in Medford proved foundational in developing his methodological philosophy, showing him the potential of the empirical microeconomist.

“The program opened my eyes to what an economist can do,” said Jagnani. He learned how such economists could answer important policy questions with clarity, ensuring that the assumptions behind their conclusions remained transparent and discernible. Today, he applies this empirical toolkit to delve deeply into sustainable development challenges faced by lower-income countries.

Jagnani’s research intersects environmental sustainability, human capital development, and poverty alleviation. His interest in these topics can be attributed not only to his “home bias” but also to his pivotal experiences as a research associate (RA) on a field experiment that evaluated a weather insurance product for small and marginal farmers in India.

“Being from India, a developing country marked by its young population and immense environmental challenges, I've always felt a strong resonance with many global sustainable development issues.”

“However, it was the two years I spent as an RA before starting my PhD that shaped my topical focus,” he added. “The hands-on experience of applying the empirical toolkit in the field to answer questions that really matter was quite satisfying.”

Environmental Adaptation in Lower-Income Countries

Today, one area of his work delves into how households in lower-income countries anticipate and adapt to extreme environmental health conditions, such as heat, air pollution, and floods.

“With extreme weather events widely projected to grow in the years ahead due to climate change, and extremely poor air quality increasingly common in developing countries, it is crucial to know if and how well disadvantaged communities can adapt to these environmental stressors,” said Jagnani. “My research examines the extent of private adaptation and tests interventions that may encourage protective behavior and defensive investments.”

In an ongoing project, Maulik is collaborating with Google’s Flood Forecasting Initiative to experimentally evaluate a cutting-edge flood forecasting and alerting system in the Ganges-Brahmaputra River basin, which plays a central role in South Asia’s vulnerability to flood disasters.

“We anticipate research insights on how to disseminate time-sensitive forecasts that encourage high-cost avoidance behavior in response to unsafe environmental health conditions,” said Jagnani.

In a similar vein, he is conducting a field experiment with randomized allocation of air purifiers in small-scale textile firms in Bangladesh to estimate the effect of air pollution on worker productivity as well as firms’ willingness to pay for defensive investments that help reduce workers’ exposure to air pollution.

“Absent significant changes in regulatory enforcement, understanding the effect of—and the willingness to pay for––such defensive investments in workplaces as well as in residential settings is paramount.”

Economic and Environmental Stressors, and Human Development

In another related area of research, Jagnani explores the consequences of poor environmental and economic conditions on human capital formation, such as education, health, and productivity.

“Human capital accumulation is an important channel through which people in low-income countries can escape poverty. However, the lives of many in low-income countries are also associated with difficult environmental and economic conditions that may directly or indirectly impede human capital production,” said Jagnani.

“For example, we recently completed a field experiment in Bangladesh to examine how heat affects team-based production relative to individual production in a high-skilled task. This relationship is of particular interest for low-income countries since team-based high skilled jobs are increasingly being undertaken in the global south, and because adoption of defensive technologies like air conditioners is extremely low in these contexts.”

Jagnani also has a keen interest in studying the causes and consequences of poor sleep in lower-income countries. “Sleep is an important input for attention, memory, and health. However, the poor invest less in sleep than those with more money,” said Jagnani.

In a working paper, he shows that this is not for lack of trying but because of poor sleep quality: financial concerns associated with poor economic conditions impede both sleep onset and sleep continuity, as well as performance on cognitive measures sensitive to sleep deprivation like memory and attention.

This fall, Jagnani will bring his insight and expertise to his course on microeconomics.

“Microeconomics provides tools to understand human behavior in real life by analyzing the decisions we make in various situations, including those that may seem non-economic at first glance,” he said.

“How do farmers in lower-income areas decide between using traditional farming methods or adopting new technologies that could increase yield but also carry risks? Or how do firms decide on the amount to invest in green technology versus pollution control equipment? Insights from microeconomics are crucial for designing effective policies and interventions that can lead to better outcomes for everyone involved.”

Read more about Fletcher’s MIB and MALD programs.