-

Hear from Professor Monica Toft

Learn how Professor Monica Toft is shaping the study of global affairs and diplomacy at Fletcher.

Hear from Prof. Toft -

Explore Fletcher academics in action

Fletcher Features offers insights, innovation, stories and expertise by scholars.

Get global insights -

Get application tips right from the source

Learn tips, tricks, and behind-the-scenes insights on applying to Fletcher from our admissions counselors.

Hear from Admissions -

Research that the world is talking about

Stay up to date on the latest research, innovation, and thought leadership from our newsroom.

Stay informed -

Meet Fletcherites and their stories

Get to know our vibrant community through news stories highlighting faculty, students, and alumni.

Meet Fletcherites -

Forge your future after Fletcher

Watch to see how Fletcher prepares global thinkers for success across industries.

See the impact -

Global insights and expertise, on demand.

Need a global affairs expert for a timely and insightful take? Fletcher faculty are available for media inquiries.

Get in Touch

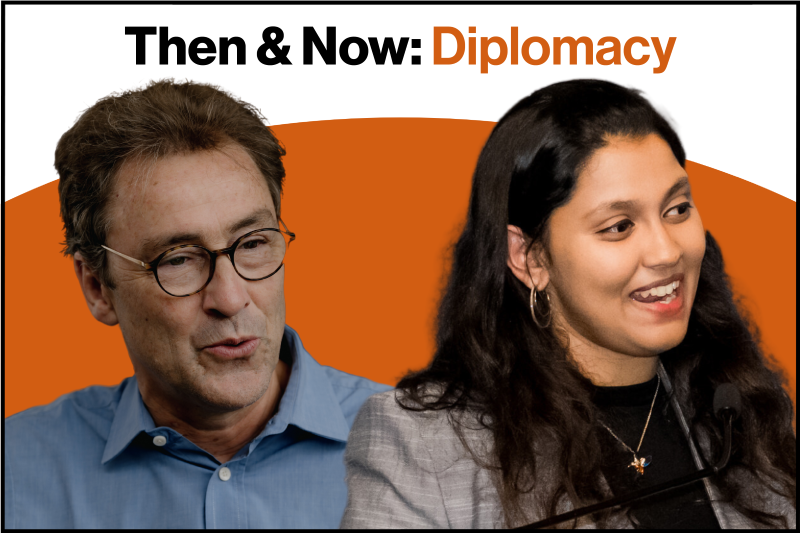

Diplomacy at Fletcher: Then and Now

Alumnus David Harland and student Akshaya Mohan reflect upon the role of diplomacy and international law in global affairs

For 90 years, The Fletcher School has been educating diplomats, leaders, and practitioners who work at the forefront of international affairs. Last year, David Harland F90 FG93 found himself at center stage during a global crisis. As the ongoing war in Ukraine jeopardized global food security, Harland helped negotiate a deal to unlock essential grains from Ukraine for export around the world.

Throughout his career, Harland has helped resolve global conflict. During his tenure at the United Nations, he worked in Bosnia, Kosovo, Haiti, and Timor Leste, and he was a former chair of the World Economic Forum conflict prevention council. Since 2011, Harland has served as the executive director of Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, an international organization that aims to resolve armed conflict through dialogue and discreet diplomacy.

Diplomacy Then: Public International Law to Untangle International Knots

Growing up in New Zealand in the 1970s, Harland was interested in finding ways to resolve violent conflict. His father Bryce Harland F55, himself a Fletcher alumnus, was a diplomat who served as the ambassador to China during the cultural revolution. Harland’s own sense of political awareness began to develop during the Vietnam War, which seemed to be on his doorstep both in New Zealand and China. Once he completed his undergraduate studies in New Zealand, he went on to study in China and subsequently worked in the United Nations. He attended Fletcher with a desire to comprehend the mechanics of the international system.

“My whole life story has been about humanity's very imperfect efforts to manage our conflict, and Fletcher sits at the center of my life story in war and peace.”

His education provided him with a framework to approach the problems he would proceed to tackle throughout his career. He still remembers a class on public international law with the late Alfred Rubin.

“Why is the world organized the way it is?” he said. “And what within that matrix can be done about it? Those questions can be applied to many areas.”

This way of thinking proved inspirational as Harland began to consider various global problems through this lens. He completed a dual degree at Harvard in East Asian Studies, and he explored his concurrent interest in conflict in China. Following graduation, he pivoted to environmental policy and worked on what became the Montreal Protocol on the ozone layer. Harland found that the questions and issues that had sparked his interest at a young age he could now reexamine through this lens of public international law.

“The world is not run the way it should be to favor its survival through various existential threats in the 21st century,” said Harland. “It has evolved into nearly 200 little parcels of territory that have a certain structure of relations between them. It’s somewhat chaotic, and sometimes very violent, but there are rules, or at least patterns of behavior, that it's important to perceive and operate within.”

At Fletcher, he was enthralled by what insight could be gleaned from scrutinizing interests and motivations in various cases, such as the Lotus case. Similarly, his “Plato to NATO” course provided him with some important understanding of state interests.

“Plato was a philosopher who believed that the world should be ruled by philosophers,” Harland said, recollecting his professor’s lecture. “The question he asked us throughout the whole course was whether, in the case that Plato had been a garbage collector, he would have suggested that the world be run by garbage collectors. In other words, what is the interaction between ideas and interests?”

Diplomacy Now: Unraveling Colonial Structures of Power

As a student at Fletcher today, Akshaya Mohan F24 scrutinizes this idea of interests as well. Coming from India, Mohan has been particularly keen on understanding the mechanisms by which international law functions in the global south, alongside its ramifications. A narrative she sees commonly promoted is that international law is less adhered to in the global south.

“I see two sides of this. On one side, the global south wants to follow these laws, probably more stringently, because they want to ascend the international hierarchical order. But on the other side, I do see a lot of countries from the global south, including mine, challenging certain elements of international law because they reflect the colonial past.”

In her studies, Mohan is interested in understanding how international law can be more equitable, whether with climate policy or nuclear power. Alongside a group of her peers, she organized the Decolonizing International Relations conference to open dialogue about colonialism in international law and whether change can be made to reframe the system.

“One of the primary ideas we're exploring is how international law carries elements of colonialism in it, and how we can break through that wheel of continuing imperialism so that the law becomes more equitable,” said Mohan.

“I’ve started focusing both on how to convince the global south to buy into international law, but also how to make international law more equitable so that the global South wants to do so,” she added.

Confronting Challenges of International Law, Today

Throughout her undergraduate studies in law, Mohan had begun to make some key observations about the efficacy of international law, and she enrolled at Fletcher to learn more.

"International law is not a regime; it is a salad bar,” she said during her recent speech at a Fletcher 90th anniversary celebration in New York City. “It has all the ingredients to make a great dish, but the challenge lies in catering to the tastes and preferences of each state. So what's the key to a great salad? It's diplomacy."

As she considered graduate programs to explore these issues, Mohan was torn between an MA and an LLM. After hearing about Fletcher’s MALD degree program, she felt she’d found her fit and that the school’s interdisciplinary focus would allow her to combine her legal background with her interest in global governance.

“I want to understand where law and diplomacy intersect,” said Mohan “The third pole of that is understanding how to engage in negotiations in that sphere. That's the reason I chose my fields of study: to understand how to uphold the law while still being diplomatic.”

Assessing the systems of international law today, Harland also sees potential for improvement.

“The systems of law and diplomacy more or less manage the world’s risk,” said Harland. “What we find is that the structures of the international system are less and less capable of coming up with the types of solution that, for example, the Cold Warriors came up with to nuclear warfare. We don't have a matrix anymore for effectively managing global risks.”

“At a time when traditional bilateral diplomacy and multilateral diplomacy are under stress, and the UN Security Council hasn't made a meaningful decision in a decade, there is a greater imperative for other actors,” he added.

“In many societies, power is moving away from governments either to private corporations or to citizens empowered by social media, but that hasn't improved the world's capacity to resolve problems. In many ways, it's made it worse. The job of the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue as a private diplomacy actor is to focus on the shared existential risks and to invest the type of knowledge capital you get at Fletcher in creative solutions to some of them.”

He pointed to the Ukraine grains deal as well as the national ceasefire in Libya, which the center reached through its intelligent methodology.

“I don't think we are going to come up with a ‘Venus from the waves’ arms control framework for the world, or make climate change go away, but there are a series of new problems that are not amenable to traditional forms of diplomacy that we can help on.”

Read more about Fletcher’s international negotiation and conflict resolution field of study and the school’s 90th anniversary.