-

Hear from Professor Monica Toft

Learn how Professor Monica Toft is shaping the study of global affairs and diplomacy at Fletcher.

Hear from Prof. Toft -

Explore Fletcher academics in action

Fletcher Features offers insights, innovation, stories and expertise by scholars.

Get global insights -

Get application tips right from the source

Learn tips, tricks, and behind-the-scenes insights on applying to Fletcher from our admissions counselors.

Hear from Admissions -

Research that the world is talking about

Stay up to date on the latest research, innovation, and thought leadership from our newsroom.

Stay informed -

Meet Fletcherites and their stories

Get to know our vibrant community through news stories highlighting faculty, students, and alumni.

Meet Fletcherites -

Forge your future after Fletcher

Watch to see how Fletcher prepares global thinkers for success across industries.

See the impact -

Global insights and expertise, on demand.

Need a global affairs expert for a timely and insightful take? Fletcher faculty are available for media inquiries.

Get in Touch

The Value of Meeting Face-to-Face

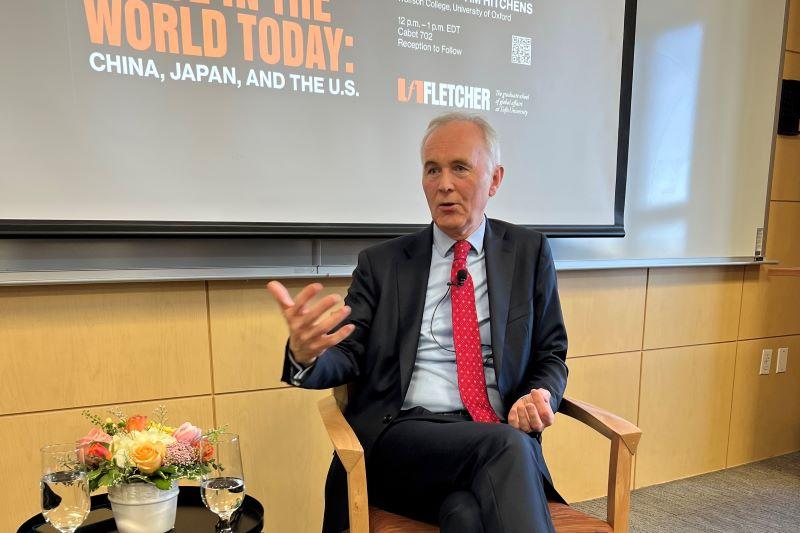

An interview with Sir Tim Hitchens, president of Wolfson College, University of Oxford

On March 27, Sir Tim Hitchens, traveled to The Fletcher School to deliver a talk, “Why East Asia is the most important place in the world today: China, Japan, and the U.S,” moderated by Academic Dean Kelly Sims Gallagher. Hitchens is the former U.K. Ambassador to Japan and the current president of Wolfson College, University of Oxford.

During his visit, The Fletcher School spoke with him about East Asian diplomacy, the United Kingdom’s role in the region, and relations between China and the United States. This conversation occurred three days before the UK announced a final deal to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

The Fletcher School: What drew you to a career in diplomacy?

Tim Hitchens: Initially, it was the ability to travel and get paid for it. I emerged from university aged 21 and longing to go to Japan. The British Foreign Service trained me in Japanese and sent me there. They would go on to send me to Pakistan, France, and around Sub-Saharan Africa. I've also always enjoyed and had a reputation for being a peacemaker, whether it's within my own family or now at Oxford University.

Commentators often talk about Western sanctions and the Western alliance. Is the role of Japan overlooked?

I think Japan would happily regard itself as a member of “the West.” The West is a term that goes beyond geography. When I was first in Japan in the 1980s, there was a strong sense that in some ways, Japan was a Western outpost that happened to be on the other side of the world. Japan’s Asian role became more emphasized in recent times as the idea of the West itself went out of fashion. People coined the phrase “Westlessness.” But over the last 12 months since the invasion of Ukraine, the West is back, and Japan is part of it.

Japan has a fraught history in East Asia. Does the Japanese alliance create difficulties for the United Kingdom or United States as they deal with other regional partners?

I don't think so. I think it depends upon whether one is honest with one's allies. If you brush problems under the carpet, it does stir up trouble. As far as the British government is concerned, when we have been unhappy with Japanese behavior, we have spoken to them about it. The death penalty is an obvious example. But I hope that in our dealings with Korea or China, the British are not seen as friends of the history of Japan. I think we've all drawn a line from 1945. Before 1945 is another world. We judge each other on what's happened since then.

South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol has been making an effort to resolve recent tensions between Japan and Korea. Can the two countries settle their dispute?

It's been a real weakness in the security architecture of East Asia that Japan and Korea have found it so difficult to find an effective modus vivendi. From the outside, they're both close allies of the U.S., are very dependent upon the U.S. economy, and face the same kind of threats from China. Still, they're not yet ready to resolve some of their emotional disputes with each other. They're not ready to put history behind them as fully as they should.

Do you see the AUKUS development as transformative for the Pacific security architecture?

For Australia or the U.K., it's a big deal. I don't think it massively changes the security architecture, because the scale of what it offers may be significant to us but is not a game changer for the nature of the threats. But I think it's a sign that what happens in East Asia matters to a lot of countries who have a significant say on the world stage.

The U.K. has also expressed interest in joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), a major trade initiative in the Asia-Pacific region.

The Japanese and the British have been working particularly hard over the last few months to make this happen. I think the key point is that geography no longer defines every aspect of trade. There are some very significant parts of trade that are as relevant to somebody sitting in Europe as they are to somebody sitting in Chile or in the Philippines.

Does it make sense for the U.K. to focus so much on the Asia-Pacific region, or does this risk neglecting relationships with neighbors in Europe?

Under Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, the engagement with the European Union is now very significant. Relations with the U.S., France, and others have improved. But the U.K. has always, in my time, been very good at understanding both the important and the urgent. The government recently issued a new international security document, and East Asia is front and center. It seems absolutely right that as a Security Council member, a country with the ability to project force very significantly, the U.K. should be interested in the most important part of the world, which is East Asia.

The U.K. will soon coronate a new head of state. As the former Assistant Private Secretary to Queen Elizabeth II, do you expect the new monarch to impact British diplomacy?

The monarchy provides stability and predictability to our system. In some ways, it's the basis that allows elected governments to take risky decisions. I think that the coronation of King Charles will be a moment of celebration and continuity, but it won't be the direct cause of any significant changes.

The British royal family have always played significant roles in diplomacy, but always on the advice of government and always in a soft way. Though it's hard to define exactly what has been achieved, it's also undeniable that something's been achieved. Particularly, relationships between the British monarch and the U.S. president have been important for the last 100 years. I've no doubt they'll continue to be.

You spoke during the talk about the importance of the U.S. and China reaching a detente like in the 1970s, rather than a new Cold War. What concrete steps can the countries take to achieve this?

If there were easy answers, it wouldn't be an important and difficult question. Setting up a regular dialogue is important. The U.S. Secretary of State should be able to visit Beijing and not get distracted by balloons. There should be guardrails that allow the presidents to meet each other. These things sound like diplomatic theater, but they are the basis for how countries can understand each other. The greatest risk is that we misunderstand each other's intentions. You can't get rid of those risks unless you're looking people in the eye and judging what they really mean. That has to start again as soon as possible.

During the pandemic, President Xi Jinping did not leave China for over two years and conducted few diplomatic engagements. Did this create a multi-year deficit in the kind of trust you’re describing?

If there's a good friend you haven't seen for three years, your level of understanding of who they are does fade. There's no doubt that COVID has set back a whole set of relationships and diplomacy, because we haven't had the chance of looking each other in the eye. There is a deficit, and it applies to the U.S.-China relationship as well as many other relationships.

I remember talking once with Douglas Hurd, one of the great U.K. Foreign Secretaries. I asked him what he thought was the single most important aspect of diplomacy, and he said judgment of somebody's character by seeing them face-to-face. There is no substitute for that.