-

Hear from Monica Toft, Academic Dean

Learn how Monica Toft, Academic Dean, is shaping the study of global affairs and diplomacy at Fletcher.

Hear from Prof. Toft -

Explore Fletcher academics in action

Fletcher Features offers insights, innovation, stories and expertise by scholars.

Get global insights -

Get application tips right from the source

Learn tips, tricks, and behind-the-scenes insights on applying to Fletcher from our admissions counselors.

Hear from Admissions -

Research that the world is talking about

Stay up to date on the latest research, innovation, and thought leadership from our newsroom.

Stay informed -

Meet Fletcherites and their stories

Get to know our vibrant community through news stories highlighting faculty, students, and alumni.

Meet Fletcherites -

Forge your future after Fletcher

Watch to see how Fletcher prepares global thinkers for success across industries.

See the impact -

Global insights and expertise, on demand.

Need a global affairs expert for a timely and insightful take? Fletcher faculty are available for media inquiries.

Get in Touch

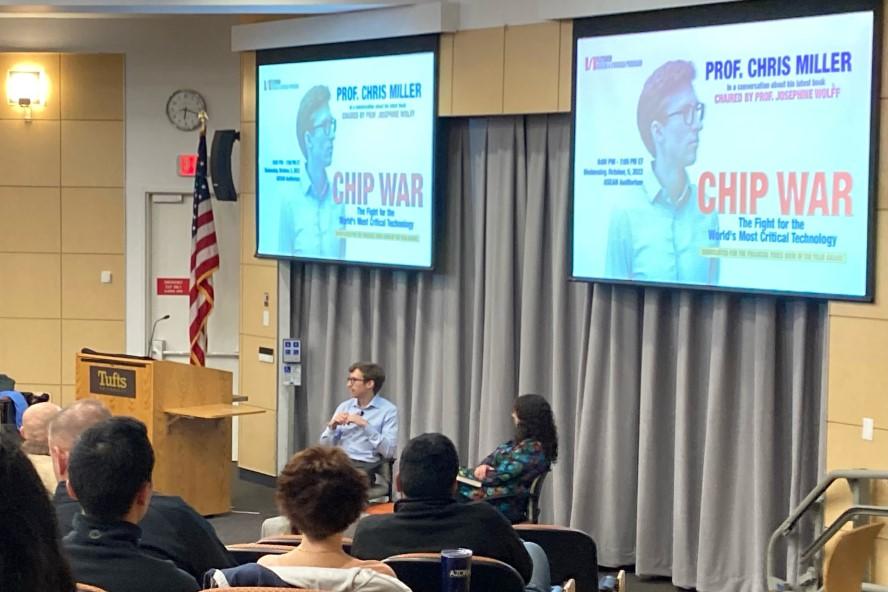

Master of Microchips

Economic historian Chris Miller examines how semiconductors drive global policy.

Semiconductors are the new oil, the commodity whose flow drives economic, political, and military decision making. For decades the battle to produce the most advanced microchips has played a key role in international relations. That's why Chris Miller, an associate professor at the Fletcher School, wrote the acclaimed new book Chip War: The Fight for the World's Most Critical Technology.

Historian Paul Kennedy, the author of The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, calls it "an eye-popping work, a unique combination of economic, technological, and strategic analysis." The product of five years of research and 150 interviews, Chip War has been hailed by The Financial Times as one of the best business books of 2022.

"A quarter of global trade is either in semiconductors or in goods that wouldn't exist if it weren't for semiconductors. This industry is more concentrated than any other, and it creates not only positions of economic influence but also geopolitical power for those who control access to this technology," says Miller.

An economic historian focused on Russia, Miller's fascination with microchips grew out of his interest in the role they played in the Cold War space race and arms race. His previous works include We Shall Be Masters: Russian Pivots to East Asia from Peter the Great to Putin (2020) and Putinomics: Power and Money in Resurgent Russia (2018). In fall 2023, Miller will teach a course on Russian foreign relations over the past 300 years and another on U.S.-Russia relations.

The U.S. plays a crucial role in the Ukraine war because it stands astride the global chip industry. Russia's high-tech weapons are inferior at least in part because they rely on microchips smuggled from the U.S., South Korea, and other countries, according to Miller, and the U.S. is trying to restrain the technological chip-making progress of China which is spending billions of dollars to catch up.

"China's leadership is deeply fearful this gives the U.S. leverage over China that can be used both during peace and war time," says Miller who is a visiting fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. "They're desperate to produce the technology their nation needs, and if China succeeds, this will reshape not only the chip industry but the global balance of power as well."

The world's most advanced chips are made in Taiwan, a fact that heightens tensions between Beijing and Washington. "It's obvious the military balance has shifted dramatically in China's favor such that it's no longer clear who would win if fighting started," he says. "I think this opens the door for Beijing to ask whether it ought to try something. So there's more uncertainly as to what the Chinese will do."

Just as chips are woven into multiple aspects of international relations, Fletcher helps students understand how these threads combine to make a bigger pattern. Fletcher and Miller have a shared belief— to understand the world you must understand its complex relationships. That's the Fletcher advantage and the reason behind its multidisciplinary approach.

"It makes Fletcher unique," says Miller. "With complicated problems, you need complex frameworks to make sense of them. Fletcher's approach to every issue is to bring multiple different analytics to bear on problems.

"One of my main goals in the classroom is to get students excited about seeing these new frameworks. Gaining new analytical purchase on difficult issues is something students finding enlightening."