-

Hear from Professor Monica Toft

Learn how Professor Monica Toft is shaping the study of global affairs and diplomacy at Fletcher.

Hear from Prof. Toft -

Explore Fletcher academics in action

Fletcher Features offers insights, innovation, stories and expertise by scholars.

Get global insights -

Get application tips right from the source

Learn tips, tricks, and behind-the-scenes insights on applying to Fletcher from our admissions counselors.

Hear from Admissions -

Research that the world is talking about

Stay up to date on the latest research, innovation, and thought leadership from our newsroom.

Stay informed -

Meet Fletcherites and their stories

Get to know our vibrant community through news stories highlighting faculty, students, and alumni.

Meet Fletcherites -

Forge your future after Fletcher

Watch to see how Fletcher prepares global thinkers for success across industries.

See the impact -

Global insights and expertise, on demand.

Need a global affairs expert for a timely and insightful take? Fletcher faculty are available for media inquiries.

Get in Touch

Leaving Nobody Behind in Afghanistan

Author and Veteran Elliot Ackerman F03 explores loyalty, accountability, and awareness in The Fifth Act.

In August of 2021, as the US withdrawal from Afghanistan and its concurrent chaos approached its conclusion, Elliot Ackerman F03 was on vacation with his family in Italy. Ackerman knew that some Afghans, not only Americans, were anxious about their own exits.

Ackerman once fought alongside them.

The former Marine became part of what has been termed a digital Dunkirk: a worldwide collaborative that used e-mail, social media, WhatsApp, Signal, and other online resources to facilitate the departures of Afghan allies and their families before the door slammed shut. Ackerman was partly driven by a principle he followed during his service: We don't leave our people behind.

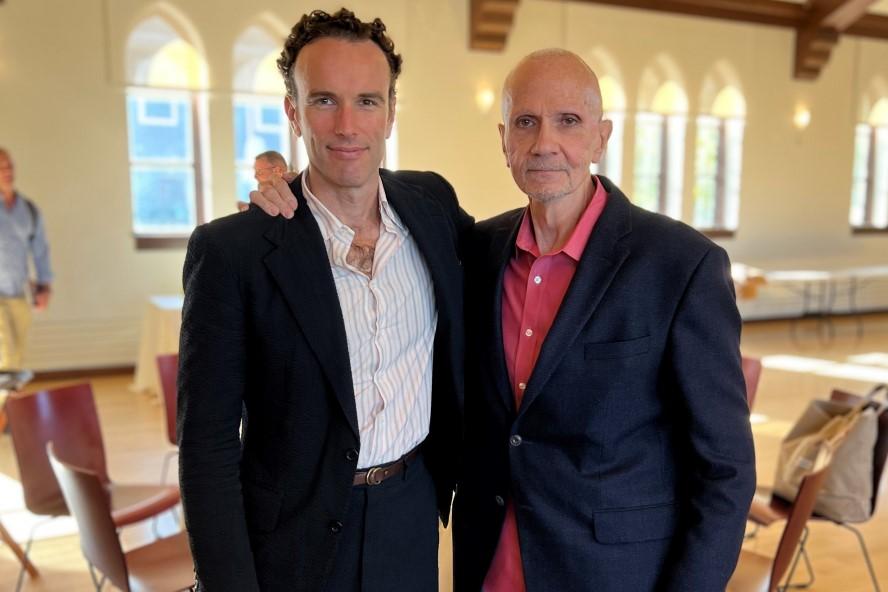

"We've all learned that," Ackerman said during a discussion with Fletcher Professor Richard Shultz on Oct. 27. "That is an ideal we try to live up to. It can often be very, very complicated. It's not an ideal that is unique in any way to the US military...it is really an ideal that is as old as war itself."

Ackerman detailed the Afghanistan withdrawal and its aftermath in The Fifth Act: America's End in Afghanistan. The title of the book refers to the five-act structure of tragedies, perhaps made most famous by William Shakespeare. Ackerman centered his acts on President Bush, President Obama, President Trump, President Biden, and the Taliban.

He wrote about the account through lenses of his past experiences, including as a Marine, CIA officer, and White House Fellow. Ackerman served five combat tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, where he received the Silver Star, the Bronze Star for Valor, and the Purple Heart.

Ackerman recalled how one of his friends died during a battle in Afghanistan. The ambush was still ongoing when his commander ordered his team to recover the body. To do so, the Marines were risking serious injury, at best, or several deaths, at worst. Eventually, a sister team recovered the body.

"We, his teammates, were not the ones who were able to do it," said Ackerman. "That certainly weighed on me. I think it weighed on a few of the rest of us. There's a marker on the wall. We reached up, we jumped and tried to touch it and couldn't quite get there. You don't always get there."

"Leave no one behind is a platitude at the end of the day," he continued. "Just because something's a platitude doesn't mean it's false, but it does mean it's a platitude. Oftentimes we go to war with platitudes in our mouths."

As such, Ackerman acknowledged that many Afghan allies awaiting visas remain in hiding in Afghanistan. Meanwhile, approximately 80,000 Afghans are in the United States – their futures are unsettled. Under the Afghan Adjustment Act, they would receive permanent residence in the US.

"It looks unlikely to pass," Ackerman said of the bill, "which is a staggering indictment of our country."

Ackerman believes that part of the problem, more than a year after the withdrawal from Afghanistan, is a general receding of national awareness. At the same time, the United States has outsourced national defense and created a subcaste, in Ackerman's words, of military service members.

Ackerman identifies one possible remedy: a draft.

"If you knew you had a one in 20 chance of your son or daughter being forced to go -- conscripted when they turn 18 or 19 -- if it was one in 20, you would be paying much closer attention to how we deployed our forces around the world," said Ackerman. "We wouldn't be having 20-year wars where no one is paying attention."

Watch the videotaped discussion.

Read more about Fletcher's Master of Arts degree program.