-

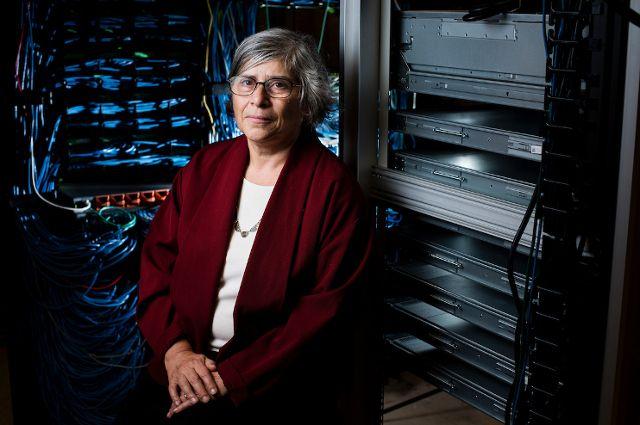

Hear from Monica Toft, Academic Dean

Learn how Monica Toft, Academic Dean, is shaping the study of global affairs and diplomacy at Fletcher.

Hear from Prof. Toft -

Explore Fletcher academics in action

Fletcher Features offers insights, innovation, stories and expertise by scholars.

Get global insights -

Get application tips right from the source

Learn tips, tricks, and behind-the-scenes insights on applying to Fletcher from our admissions counselors.

Hear from Admissions -

Research that the world is talking about

Stay up to date on the latest research, innovation, and thought leadership from our newsroom.

Stay informed -

Meet Fletcherites and their stories

Get to know our vibrant community through news stories highlighting faculty, students, and alumni.

Meet Fletcherites -

Forge your future after Fletcher

Watch to see how Fletcher prepares global thinkers for success across industries.

See the impact -

Global insights and expertise, on demand.

Need a global affairs expert for a timely and insightful take? Fletcher faculty are available for media inquiries.

Get in Touch

Contact-tracing apps have serious physical, biological limitations

Susan Landau explains the pitfalls of contact-tracing apps and the challenges they pose to public health amid COVID-19 recovery, via an excerpt from her book "People Count: Contact-Tracing Apps and Public Health" in Big Think.

[...]

By helping to keep spread in check, could contact-tracing apps have lowered R0 enough to allow people to safely work, participate in social life, and be with their families? Lacking a real-life human experiment to answer this question, epidemiologists turn to models; these are in turn based on existing data. In the case of COVID-19, some of the best data comes from a citizen-science app developed by the BBC to accompany its 2018 documentary on the Spanish flu, Contagion! The BBC4 Pandemic. Participants agreed to provide a twenty-four-hour snapshot of their locations and self-reported contacts, which epidemiologists then used to model how a similar epidemic would spread in twenty-first-century Britain.

The BBC database ultimately included the locations and contacts of 36,000 people. It showed their movements over the course of a day, including how many people they saw at work, at school, and elsewhere. The data allowed researchers to develop a model that could simulate various interventions at the population level, from isolation, testing, contact tracing, and social distancing to app usage.

The resulting model showed that if 90 percent of ill people self-isolated and their household quarantined upon learning of their infection, 35 percent of cases would have already spread the disease to another person. If 90 percent of the contacts of those infected also isolated upon learning of the previous person's infection, only 26 percent of cases would have infected someone else. The contact tracers, in other words, bought time. By having potentially infected people isolate, contact tracing prevented new rounds of infections. In another iteration, the researchers added apps to the mix and assumed that 53 percent of the population would use them. By notifying people of potential infections faster than a contact tracer could, the apps lowered the infection rate further, so that only 23 percent of cases infected another person. At that high adoption rate, the disease doesn't disappear, but it also doesn't cause a pandemic.

Models, of course, are only as good as the assumptions on which they're based. The idea that 53 percent of any given population would voluntarily use a contact-tracing app and that anyone receiving an exposure notification would isolate is doubtful, at best. Still, because the apps appear to help lower R0, governments and public health officials have jumped to add them to the mix of public health tools available to combat COVID-19's spread.